The ancient Chinese method of execution known as lingchi (or ling chi), is perhaps better known by the more descriptive, “death by a thousand cuts.”

As the name implies, this was a form of torture that involved slicing into the victim over and over again until they died. It was normally saved for the very worst crimes. As a form of execution, lingchi was not administered lightly.

As barbaric as it sounds, the truth about lingchi is often obscured by a popular mythology that has turned what is an already gruesome way to die into something straight out of a nightmare.

In this article, we’ll look at what lingchi is, where it came from, and what we still get wrong about this ancient practice.

Dying by Lingchi

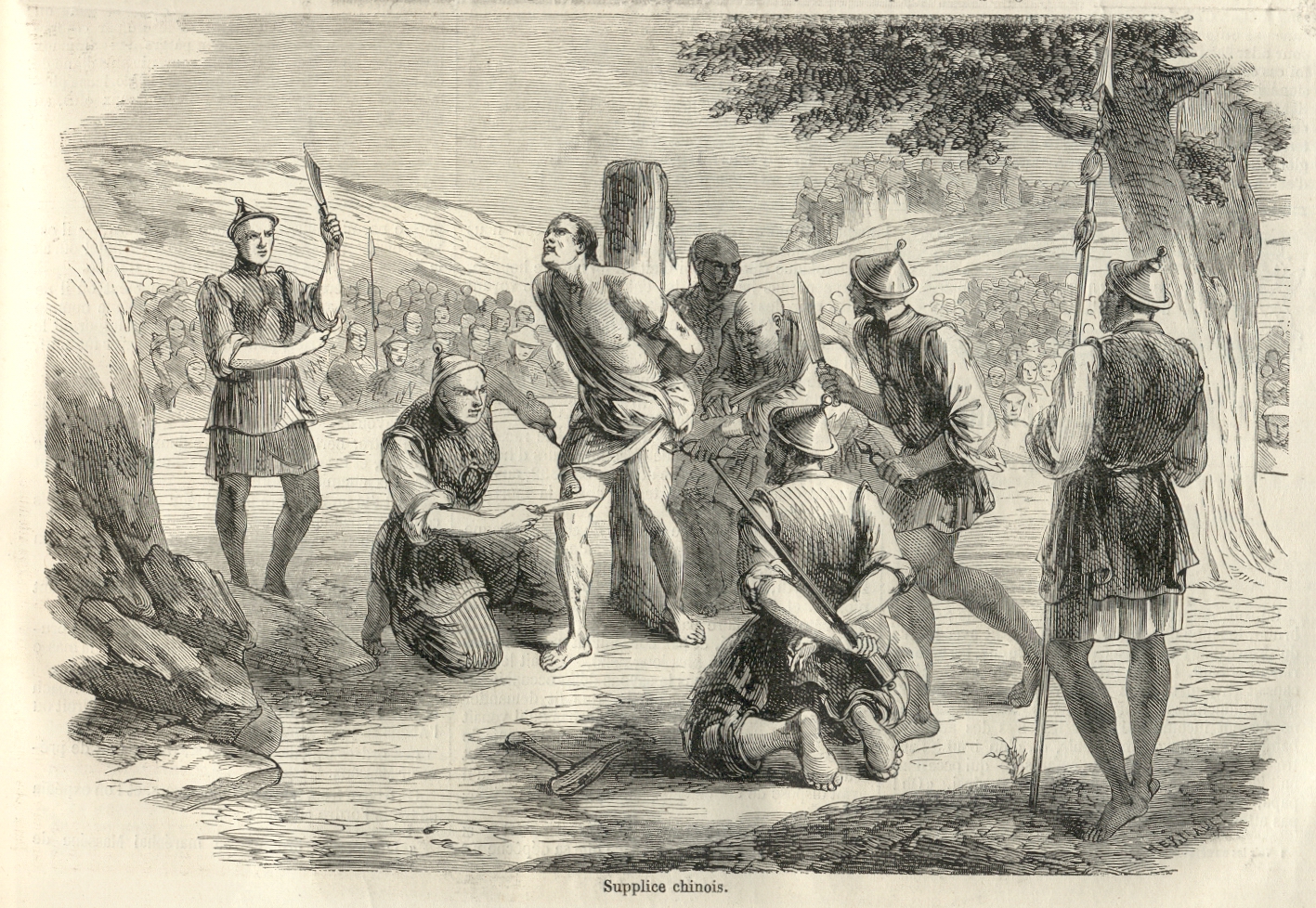

Lingchi began by tying the victim to a wooden pole or frame. Once bound, various executioners would take turns methodically slicing into different body parts.

Whether the executioners started with the chest, the arms, or the legs, was most likely up to their own discretion. But either way, it would have been agony for the person forced to endure the pain of being butchered alive.

Lingchi was cruel in more ways than just the physical pain, however.

According to the prevailing Confucianism, it was wrong to desecrate or cut up a person’s body. Thus, as the victim was being cut to ribbons, they would also die knowing they had not lived up to the principles of Confucianism.

Add to this the humiliation of experiencing all of this in public, and you can start to see why lingchi was regarded as so awful.

The Origins of Lingchi

As a method of execution, lingchi dates back centuries.

One of the earliest examples is from Prince Liu Ziye. It is said that he ordered several officials to be killed by lingchi before he was ordered by the emperor to commit suicide. Liu Ziye was an early exception, as he was a man known for his cruelty and penchant for killing at a whim.

In general, it seems that lingchi was saved for only the most egregious crimes. But when lingchi was meted out as punishment, it no doubt left a lasting impression.

You could say that the high-water mark for lingchi occurred during the Liao and Song dynasties.

As an indication of just how prevalent it became, in the 12th century, one anti-lingchi activist felt compelled to write a damning criticism of the practice, arguing that:

When the muscles of the flesh are already taken away, the breath of life is not yet cut off, liver and heart are still connected, seeing and hearing still exist. It affects the harmony of nature, it is injurious to a benevolent government, and does not befit a generation of wise men.

Unfortunately, his calls to end lingchi would go unheeded for eight more centuries.

Lingchi in the Modern World

To many people, lingchi can seem absurdly cruel and barbaric – a relic of the medieval age that never should have survived into the supposedly civilized 19th and 20th centuries.

Yet it did survive. And with the arrival of cameras and mass printing, the awareness of lingchi spread throughout the world, shocking Westerners.

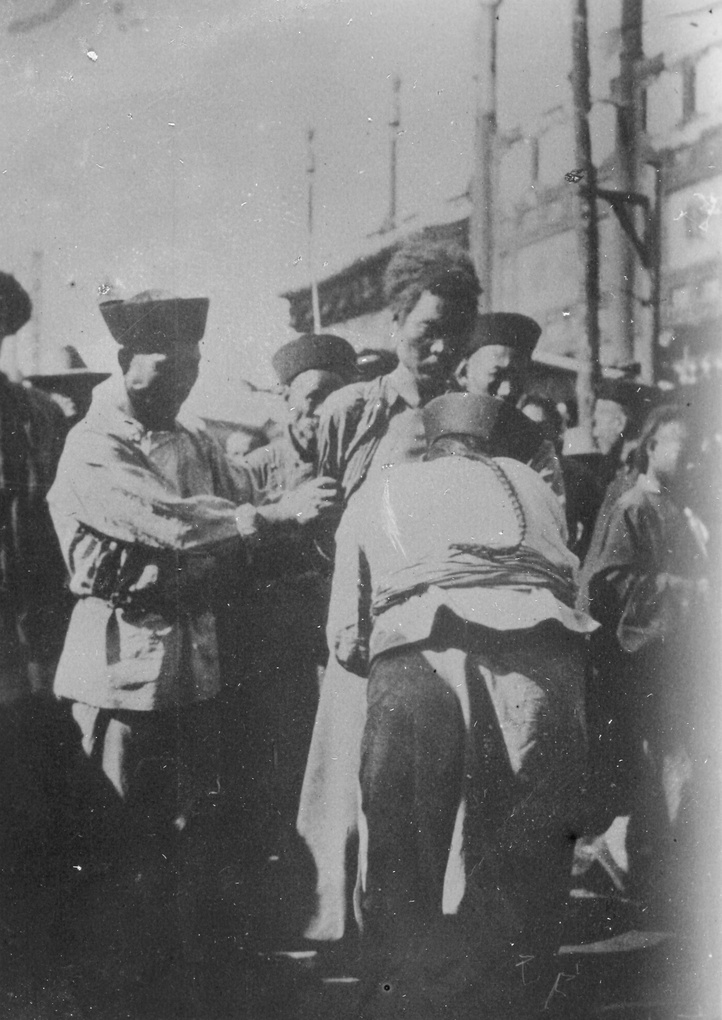

One of the earliest instances of lingchi finding its way to the West occurred in 1890 when a British captain was touring the city of Canton. As he strolled through the streets, the noise of a bustling crowd reached his ears.

As he followed the sound, it grew louder. Pretty soon he was standing at the edge of a throng of people all circling a strange object lying on the ground in the middle of the market.

As the captain drew closer, he felt his stomach drop as he recognized what the object was. It was a bloody and dismembered human, strewn across the ground.

The torso was full of deep slices, while the hands, legs, and head were all separated from the rest of the body. As discreetly as he could, the captain drew his camera, snapped a picture, and hurried back to his ship.

Lingchi in the Western World

That picture became famous in countries like the United States and Britain.

It was circulated widely in the book, The Peoples and Politics of the Far East, which was written by journalist Sir Henry Norman and published in 1895. This is the description that readers of Norman’s book would have come across:

The criminal is fastened to a rough cross, and the executioner, armed with a sharp knife, begins by grasping handfuls from the fleshy parts of the body, such as the thighs and the breasts, and slicing them off. After this, he removes the joints and the excrescences of the body one by one—the nose and ears, fingers and toes. Then the limbs are cut off piecemeal at the wrists and the ankles, the elbows and knees, the shoulders and hips. Finally, the victim is stabbed to the heart and his head cut off.

The description was accompanied by the British naval captain’s photo. It was deemed to be so graphic that the page was made to be easily ripped out by the reader, in case it was necessary.

These kinds of graphic descriptions of lingchi, when filtered through to the West, excited the collective imagination. It fuelled a mythology that greatly misconstrued what lingchi was.

It also cemented an already widespread view of Chinese people as having been stymied in their progress by a backward culture.

Some of the misconceptions arose from the translation of the word “lingchi” from Chinese. Many Westerners translate it as “death by 10,000 cuts,” or “death by a thousand cuts,” making lingchi sound like a more excruciating ordeal than it was.

Although there is no doubt that lingchi was an extraordinarily unpleasant way to die, most of the cutting was done after the victim had already died.

The first cuts to the body were normally large. This meant that the person would not be able to stay conscious for long due to so much blood loss. What’s more, some families could afford to pay for a coup de grace or to provide large quantities of opium to ease the victim’s suffering.

Still, the imagery surrounding lingchi was too strong in the West to be diluted by reality. Today, lingchi is still known more commonly as “death by a thousand cuts.” It is seen as a symbol of the more barbaric side of Chinese culture.

The last known instance of lingchi occurred in the Fall of 1904, to punish a wealthy landowner who killed his neighbor and eleven of his family members.

French soldiers in the area photographed the event. Once again, Western countries were flooded with graphic evidence of a China that was unimaginably cruel and backward.

Lingchi was officially abolished the following year. But its legacy – mythology and all – has remained ingrained in the popular imagination ever since.